This station site is in the middle of a business area, suggesting world trade and commerce. The windscreens, with their photographic images of oak trees on glass, are a blend of contemporary western industrial structures and images reminiscent of Japanese prints. It is common in traditional Japanese prints to have tree branches framing the landscape or characters that are the main subject. Oak trees were chosen because of the oak savannahs that were common along the nearby Mississippi River.

Tokuriki, Tomikichiro, The Cherry Blossoms of Mt. Shigi in Nara Prefecture

Oak Savannah

JoAnn Verburg is an American photographer who uses large format cameras to shoot life-size portraits, still life's and landscapes. Verburg’s images create narrative sequences that generate a state of prolonged experience; not a state of motion, but, rather, how we view images, as in mirroring the eye’s movement during the act of looking.

She made a name for herself in the late 1970s with “The Rephotographic Survey Project,” a collaborative exhibition and book that recreated more than 120 images of largely uninhabited Western landscapes in the 19th century. Using cameras, lenses and film that approximated the technology of their 19th-century predecessors, they waited for weather conditions that replicated the light in the original photographs, then rephotographed each place. The resulting then-and-now comparisons showed what the passage of time had done to those vistas. Surprisingly, what endured — the same trees, boulders and riverbeds — was often just as poignant as the changes to the landscape over time.

Verburg studied at Ohio Wesleyan University, earning her Bachelor’s of Arts in Sociology. She earned her Masters of Fine Art in Photography from the Rochester Institute of Photography, New York. Verburg moved to Minnesota in 1981 where she was an artist-in-residence at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. She splits her time between St. Paul, Minnesota and Spoleto, Italy.

joannverburg.com

Sacred Springs x 4, 2013

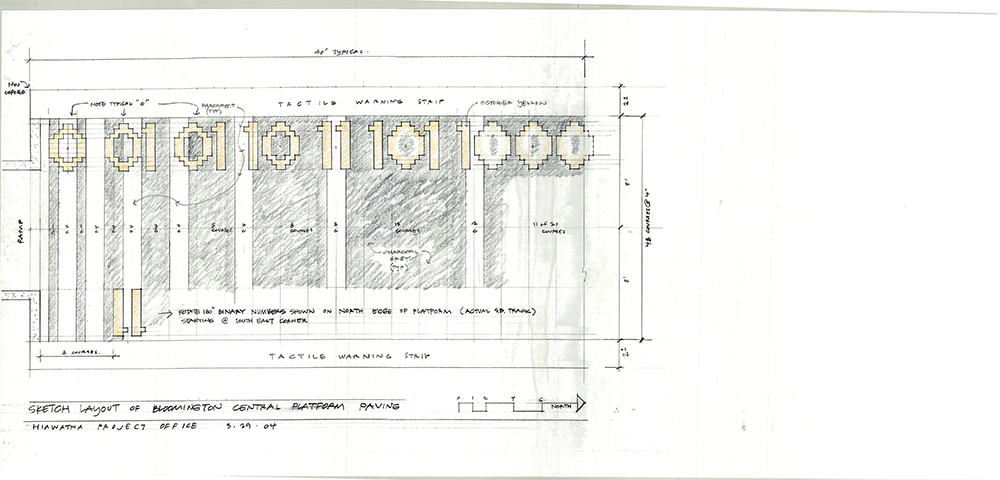

As part of the original construction, Larson had designed a paver pattern for the 28th Avenue, Bloomington Central and Fort Snelling Station platforms. The designs were installed, but unfortunately, the paver bricks did not hold up well with the severe Minnesota winters and the heavy foot traffic of a transit system. Artist Richard Elliott had also designed paver platforms for six additional stations. The only remaining platform paver design exists at American Boulevard Station.

Larson’s design for Bloomington Central Station's platform was based on computer language of 1’s and 0’s. Located near to the station are several companies that deal with data. Larson is reflecting this in his choice of using computer language as a pattern along the edges of the platform.